By Maged Hebtah

Translated by Abdelazim R. Abdelazim

09/08/2004

How did a young man born in 1933 in Aleppo (Halab), Syria’s second largest city, become attached to the cinema? And how did he make his way to the United States in 1954?

Al-Akkad relates his story with a calmness conjuring up the coziness of dear reminiscences of a man who has chosen to cling to his origins. He reveals that his love for the cinema stems from a small cinema that was owned by one of his old neighbors.

“I always accompanied that man; I used to watch how he cut the scenes and put the film into the projection device. It was my passion in life. Gradually I started dreaming of becoming a moviemaker. When I turned 18 I started announcing my enthusiasm to become a film director, and not just any director; a Hollywood director. The whole Aleppo neighborhood used to laugh and make fun of me.”

California Dreaming

Al-Akkad affirms that he does not blame his neighbors for thinking he was crazy. The dream, in a way, was a kind of craziness. “In addition to the fact that a job in the movie world was socially unacceptable,” Al-Akkad explains, “my father was a poor man. The best he could do was enroll me in an American school. However, despite the mockery of others, I didn’t give up my dream and began to take steps towards its fulfillment, one of which was applying to UCLA (University of California atLos Angeles). It came as a great surprise when my application was accepted!”

I ask about what his family thought of all this and expect the response narrated by most actors and actresses who relate the story of their early steps towards stardom: that his family strongly opposed the idea and that his father tried to convince him to forget about his dream altogether.

However, Al-Akkad’s story does not fit the general paradigm. “My father brought me up on the principle of self-reliance. His comment was, ‘You should do what you want to do and choose to live your life as you wish; but I’m afraid I cannot help you financially.’ Thus, I was forced to work for a year to be able to pay for my education. After this year I told my father I would be traveling to the United States. He put $200 into one of my pockets and a copy of the Holy Qur’an into the other and said, ‘This is all I can give you.’ However, he had already given me the most invaluable of things; he brought me up to be morally and religiously mature and responsible. Whenever I remember him, I praise Allah for having blessed me with this father, who sent me to America penniless but rich in morality, religion, and heritage—the reasons I still cherish my Arab Muslim background.”

Inferiority Complex

I asked him whether being an Arab called Mustapha caused him any trouble in America.

“Of course, there were many troubles, but they were not initiated by those around me. The problem was inside of me. I went to the United States laden with inferiority complexes because I wrongly thought I was inferior to those around me, that they were far more intelligent than me, and that it would be difficult or even impossible to emulate them. However, once I sat at my desk and mingled with other international students, I found that being an Arab Muslim did not make me inferior in any way. Conversely, I realized from the very first class that there had never been a difference between me and any Western student, and that I possessed the qualities that would make me surpass them. When I studied society there, I realized that I was morally stronger than them and truly appreciated the moral values with which my father had raised me. After this illumination, I experienced a transformation in my way of thinking, and the inferiority complexes turned into self-confidence. From that point onwards, I began studying Arab-Islamic civilization to deepen my sense of self-confidence and awareness that we had been leading the world at a time the West was inhabited by a group of barbaric tribes. I learned that we had been much more advanced in many branches of knowledge while they were in a state of ignorance and backwardness. These are the themes I have ever since been trying to visualize on the big screen: portraying the days in which we ruled Andalusia, taught the ‘barbaric’ and ignorant Europeans the sciences of astronomy and medicine, and helped them to put their feet on the ladder of civilization.”

So, what about your name specifically, I asked again.

“As far as my name is concerned,” he replied, “there is no doubt that it has caused me severe problems, to the extent that many have advised me to change it so that I could practice my work more easily. I resolutely refused. I firmly believe that changing the name chosen for me by my father would mean rejecting my identity as well as the man who raised me. I realized that the worst my name could do to me was to make me more determined to exert effort to increase the demand for me. I worked incessantly to gain the respect of my colleagues and audience. I’d like to highlight the fact that others won’t respect you unless you respect yourself.

“Those Arabs who come to the United States, change their names, and deny their Arabic tongue only to make more money disgust me. This opportunism is due to inferiority complexes that they are not managing to get rid of. They simply assimilate completely and deny everything, even their own selves; they forget themselves.”

I asked him, “You cherish your name and work hard to distinguish yourself; how did you manage to achieve this?”

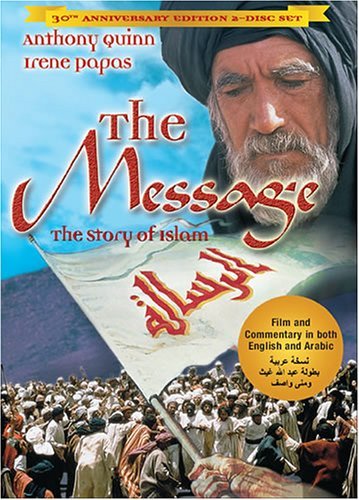

“I armed myself as a cinema director and leaned on my Arab Islamic background, which provided me with the creative capacity to learn to command the secrets of the seventh art and the American cinema, which dominates internationally. Praise be to Allah, I managed to firmly enforce my artistic presence because I mastered my cinematic language and instruments. I believe this is reflected in The Message and Lion of the Desert. The Message acquainted Western society with the true Islamic religion and Lion of the Desert very credibly reflects the current tragic situation in Palestine!”

I ask Al-Akkad what his presence in Hollywood has accomplished for him in the movie industry. He says, “They now know for sure that I can make profit-reaping, audience-attracting movies. That’s why their studios seek my experience. Universal Studios asked to me to direct Halloween 8, and many other production companies seek my professionalism.”

During the interview, a young man resembling Al-Akkad greets us. Al-Akkad introduces him as his son Malik and says, “He has been fond of cinema direction ever since he was a child and specialized in it. Considering his young age, he has already overtaken me. He participated in directing Halloween very distinctively. Because he can communicate with and understand the youth better than me, I always ask his opinion whenever I want to address them. He will assist me in directing Saladin. Even though he has been raised in America, he attaches much value to his Arabic background and origin.”

Perhaps he notices the surprise on my face, so he says, “Don’t be astonished. If you visit my home, you’ll feel as if you are in Aleppo —its atmosphere, food, music, language, and religion. However, when I go out and close the door behind me, I become an all-American man in my way of thinking, practicality, logic, work ethics, and everything else.”

Source: Islam Online

[+/-] Baca Lagi

[+/-] Ringkasan